Sigmund Freud’s Theories

Sigmund Freud’s Theories

By Saul McLeod, updated 2018

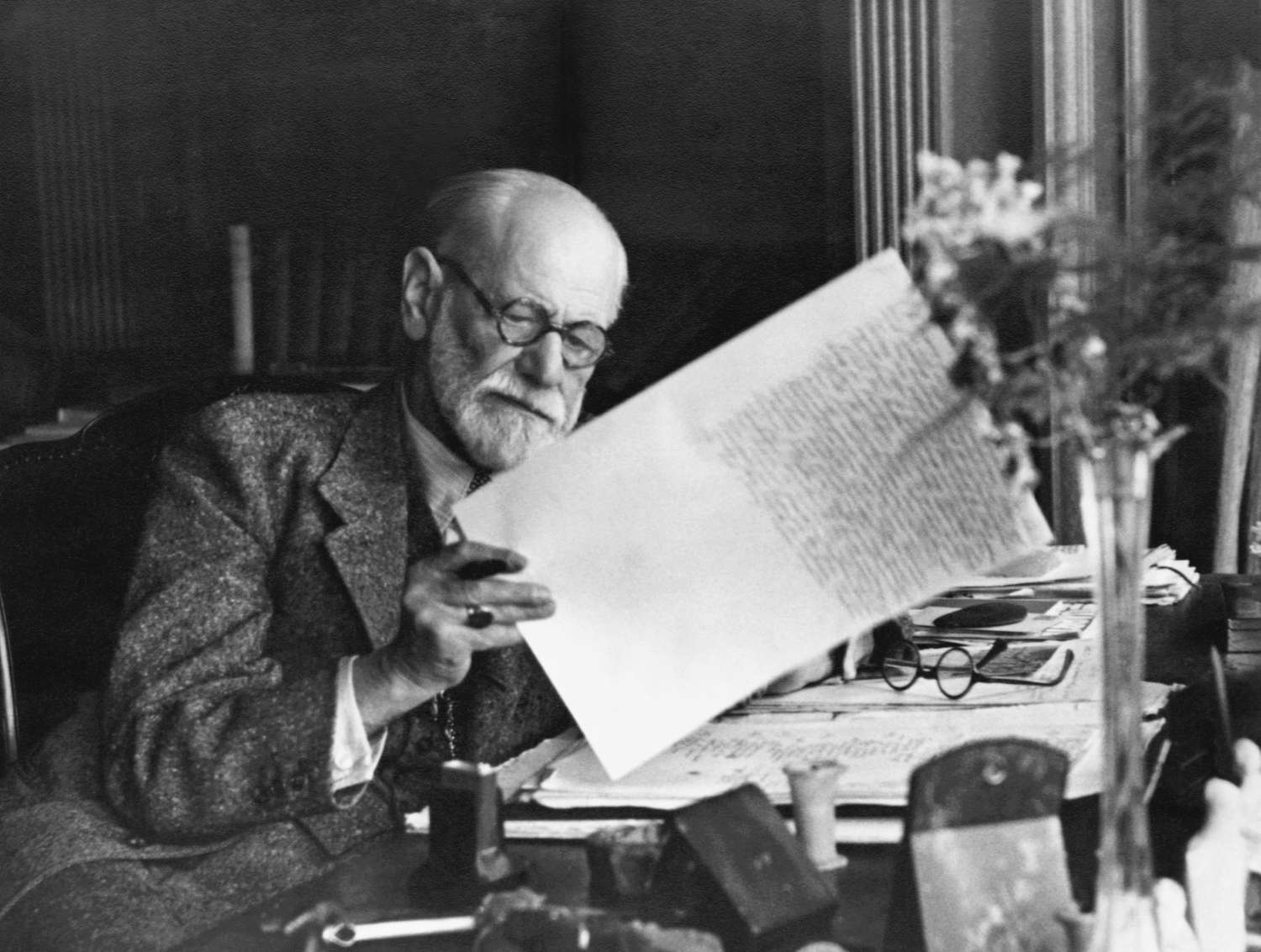

Sigmund Freud (1856 to 1939) was the founding father of psychoanalysis, a method for treating mental illness and also a theory which explains human behavior.

Freud believed that events in our childhood have a great influence on our adult lives, shaping our personality. For example, anxiety originating from traumatic experiences in a person’s past is hidden from consciousness, and may cause problems during adulthood (in the form of neuroses).

Thus, when we explain our behavior to ourselves or others (conscious mental activity), we rarely give a true account of our motivation. This is not because we are deliberately lying. While human beings are great deceivers of others; they are even more adept at self-deception.

Freud’s life work was dominated by his attempts to find ways of penetrating this often subtle and elaborate camouflage that obscures the hidden structure and processes of personality.

His lexicon has become embedded within the vocabulary of Western society. Words he introduced through his theories are now used by everyday people, such as anal (personality), libido, denial, repression, cathartic, Freudian slip, and neurotic.

The Case of Anna O

The Case of Anna O

The case of Anna O (real name Bertha Pappenheim) marked a turning point in the career of a young Viennese neuropathologist by the name of Sigmund Freud. It even went on to influence the future direction of psychology as a whole.

Anna O. suffered from hysteria, a condition in which the patient exhibits physical symptoms (e.g., paralysis, convulsions, hallucinations, loss of speech) without an apparent physical cause. Her doctor (and Freud’s teacher) Josef Breuer succeeded in treating Anna by helping her to recall forgotten memories of traumatic events.

During discussions with her, it became apparent that she had developed a fear of drinking when a dog she hated drank from her glass. Her other symptoms originated when caring for her sick father.

She would not express her anxiety for her his illness but did express it later, during psychoanalysis. As soon as she had the opportunity to make these unconscious thoughts conscious her paralysis disappeared.

Breuer discussed the case with his friend Freud. Out of these discussions came the germ of an idea that Freud was to pursue for the rest of his life. In Studies in Hysteria (1895) Freud proposed that physical symptoms are often the surface manifestations of deeply repressed conflicts.

However, Freud was not just advancing an explanation of a particular illness. Implicitly he was proposing a revolutionary new theory of the human psyche itself.

This theory emerged “bit by bit” as a result of Freud’s clinical investigations, and it led him to propose that there were at least three levels of the mind.

The Unconscious Mind

The Unconscious Mind

Freud (1900, 1905) developed a topographical model of the mind, whereby he described the features of the mind’s structure and function. Freud used the analogy of an iceberg to describe the three levels of the mind.

On the surface is consciousness, which consists of those thoughts that are the focus of our attention now, and this is seen as the tip of the iceberg. The preconscious consists of all which can be retrieved from memory.

The third and most significant region is the unconscious. Here lie the processes that are the real cause of most behavior. Like an iceberg, the most important part of the mind is the part you cannot see.

The unconscious mind acts as a repository, a ‘cauldron’ of primitive wishes and impulse kept at bay and mediated by the preconscious area.

For example, Freud (1915) found that some events and desires were often too frightening or painful for his patients to acknowledge, and believed such information was locked away in the unconscious mind. This can happen through the process of repression.

Sigmund Freud emphasized the importance of the unconscious mind, and a primary assumption of Freudian theory is that the unconscious mind governs behavior to a greater degree than people suspect. Indeed, the goal of psychoanalysis is to make the unconscious conscious.

The Psyche

The Psyche

Freud (1923) later developed a more structural model of the mind comprising the entities id, ego, and superego (what Freud called “the psychic apparatus”). These are not physical areas within the brain, but rather hypothetical conceptualizations of important mental functions.

The id, ego, and superego have most commonly been conceptualized as three essential parts of the human personality.

Freud assumed the id operated at an unconscious level according to the pleasure principle (gratification from satisfying basic instincts). The id comprises two kinds of biological instincts (or drives) which Freud called Eros and Thanatos.

Eros, or life instinct, helps the individual to survive; it directs life-sustaining activities such as respiration, eating, and sex (Freud, 1925). The energy created by the life instincts is known as libido.

In contrast, Thanatos or death instinct, is viewed as a set of destructive forces present in all human beings (Freud, 1920). When this energy is directed outward onto others, it is expressed as aggression and violence. Freud believed that Eros is stronger than Thanatos, thus enabling people to survive rather than self-destruct.

The ego develops from the id during infancy. The ego’s goal is to satisfy the demands of the id in a safe a socially acceptable way. In contrast to the id, the ego follows the reality principle as it operates in both the conscious and unconscious mind.

The superego develops during early childhood (when the child identifies with the same sex parent) and is responsible for ensuring moral standards are followed. The superego operates on the morality principle and motivates us to behave in a socially responsible and acceptable manner.

The basic dilemma of all human existence is that each element of the psychic apparatus makes demands upon us that are incompatible with the other two. Inner conflict is inevitable.

For example, the superego can make a person feel guilty if rules are not followed. When there is a conflict between the goals of the id and superego, the ego must act as a referee and mediate this conflict. The ego can deploy various defense mechanisms (Freud, 1894, 1896) to prevent it from becoming overwhelmed by anxiety.

Defense Mechanisms

Click here for more information on defense mechanisms.

Psychosexual Stages

Psychosexual Stages

In the highly repressive “Victorian” society in which Freud lived and worked women, in particular, were forced to repress their sexual needs. In many cases, the result was some form of neurotic illness.

Freud sought to understand the nature and variety of these illnesses by retracing the sexual history of his patients. This was not primarily an investigation of sexual experiences as such. Far more important were the patient’s wishes and desires, their experience of love, hate, shame, guilt and fear – and how they handled these powerful emotions.

It was this that led to the most controversial part of Freud’s work – his theory of psychosexual development and the Oedipus complex.

Freud believed that children are born with a libido – a sexual (pleasure) urge. There are a number of stages of childhood, during which the child seeks pleasure from a different ‘object.’

To be psychologically healthy, we must successfully complete each stage. Mental abnormality can occur if a stage is not completed successfully and the person becomes ‘fixated’ in a particular stage. This particular theory shows how adult personality is determined by childhood experiences.

Dream Analysis

Dream Analysis

Freud (1900) considered dreams to be the royal road to the unconscious as it is in dreams that the ego’s defenses are lowered so that some of the repressed material comes through to awareness, albeit in distorted form. Dreams perform important functions for the unconscious mind and serve as valuable clues to how the unconscious mind operates.

On 24 July 1895, Freud had his own dream that was to form the basis of his theory. He had been worried about a patient, Irma, who was not doing as well in treatment as he had hoped. Freud, in fact, blamed himself for this, and was feeling guilty.

Freud dreamed that he met Irma at a party and examined her. He then saw a chemical formula for a drug that another doctor had given Irma flash before his eyes and realized that her condition was caused by a dirty syringe used by the other doctor. Freud’s guilt was thus relieved.

Freud interpreted this dream as wish-fulfillment. He had wished that Irma’s poor condition was not his fault and the dream had fulfilled this wish by informing him that another doctor was at fault. Based on this dream, Freud (1900) went on to propose that a major function of dreams was the fulfillment of wishes.

Freud distinguished between the manifest content of a dream (what the dreamer remembers) and the latent content, the symbolic meaning of the dream (i.e., the underlying wish). The manifest content is often based on the events of the day.

The process whereby the underlying wish is translated into the manifest content is called dreamwork. The purpose of dreamwork is to transform the forbidden wish into a non-threatening form, thus reducing anxiety and allowing us to continue sleeping. Dreamwork involves the process of condensation, displacement, and secondary elaboration.

The process of condensation is the joining of two or more ideas/images into one. For example, a dream about a man may be a dream about both one’s father and one’s lover. A dream about a house might be the condensation of worries about security as well as worries about one’s appearance to the rest of the world.

Displacement takes place when we transform the person or object we are really concerned about to someone else. For example, one of Freud’s patients was extremely resentful of his sister-in-law and used to refer to her as a dog, dreamed of strangling a small white dog.

Freud interpreted this as representing his wish to kill his sister-in-law. If the patient would have really dreamed of killing his sister-in-law, he would have felt guilty. The unconscious mind transformed her into a dog to protect him.

Secondary elaboration occurs when the unconscious mind strings together wish-fulfilling images in a logical order of events, further obscuring the latent content. According to Freud, this is why the manifest content of dreams can be in the form of believable events.

In Freud’s later work on dreams, he explored the possibility of universal symbols in dreams. Some of these were sexual in nature, including poles, guns, and swords representing the penis and horse riding and dancing representing sexual intercourse.

However, Freud was cautious about symbols and stated that general symbols are more personal rather than universal. A person cannot interpret what the manifest content of a dream symbolized without knowing about the person’s circumstances.

‘Dream dictionaries’, which are still popular now, were a source of irritation to Freud. In an amusing example of the limitations of universal symbols, one of Freud’s patients, after dreaming about holding a wriggling fish, said to him ‘that’s a Freudian symbol – it must be a penis!’

Freud explored further, and it turned out that the woman’s mother, who was a passionate astrologer and a Pisces, was on the patient’s mind because she disapproved of her daughter being in analysis. It seems more plausible, as Freud suggested, that the fish represented the patient’s mother rather than a penis!

Freud’s Followers

Freud’s Followers

Freud attracted many followers, who formed a famous group in 1902 called the “Psychological Wednesday Society.” The group met every Wednesday in Freud’s waiting room.

As the organization grew, Freud established an inner circle of devoted followers, the so-called “Committee” (including Sàndor Ferenczi, and Hanns Sachs (standing) Otto Rank, Karl Abraham, Max Eitingon, and Ernest Jones).

At the beginning of 1908, the committee had 22 members and renamed themselves the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society.

Critical Evaluation

Critical Evaluation

Is Freudian psychology supported by evidence? Freud’s theory is good at explaining but not at predicting behavior (which is one of the goals of science). For this reason, Freud’s theory is unfalsifiable – it can neither be proved true or refuted. For example, the unconscious mind is difficult to test and measure objectively. Overall, Freud’s theory is highly unscientific.

Despite the skepticism of the unconscious mind, cognitive psychology has identified unconscious processes, such as procedural memory (Tulving, 1972), automatic processing (Bargh & Chartrand, 1999; Stroop, 1935), and social psychology has shown the importance of implicit processing (Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). Such empirical findings have demonstrated the role of unconscious processes in human behavior.

However, most of the evidence for Freud’s theories are taken from an unrepresentative sample. He mostly studied himself, his patients and only one child (e.g., Little Hans). The main problem here is that the case studies are based on studying one person in detail, and with reference to Freud, the individuals in question are most often middle-aged women from Vienna (i.e., his patients). This makes generalizations to the wider population (e.g., the whole world) difficult. However, Freud thought this unimportant, believing in only a qualitative difference between people.

Freud may also have shown research bias in his interpretations – he may have only paid attention to information which supported his theories, and ignored information and other explanations that did not fit them.

However, Fisher & Greenberg (1996) argue that Freud’s theory should be evaluated in terms of specific hypotheses rather than as a whole. They concluded that there is evidence to support Freud’s concepts of oral and anal personalities and some aspects of his ideas on depression and paranoia. They found little evidence of the Oedipal conflict and no support for Freud’s views on women’s sexuality and how their development differs from men’.

How to reference this article:

How to reference this article:

McLeod, S. A. (2018, April 05). What are the most interesting ideas of Sigmund Freud? Simply Psychology. www.simplypsychology.org/Sigmund-Freud.html

APA Style References

Bargh, J. A., & Chartrand, T. L. (1999). The unbearable automaticity of being. American psychologist, 54(7), 462.

Breuer, J., & Freud, S. (1895). Studies on hysteria. Standard Edition 2: London.

Fisher, S., & Greenberg, R. P. (1996). Freud scientifically reappraised: Testing the theories and therapy. John Wiley & Sons.

Freud, S. (1894). The neuro-psychoses of defence. SE, 3: 41-61.

Freud, S. (1896). Further remarks on the neuro-psychoses of defence. SE, 3: 157-185.

Freud, S. (1900). The interpretation of dreams. S.E., 4-5.

Freud, S. (1915). The unconscious. SE, 14: 159-204.

Freud, S. (1920). Beyond the pleasure principle. SE, 18: 1-64.

Freud, S. (1923). The ego and the id. SE, 19: 1-66.

Freud, S. (1925). Negation. Standard edition, 19, 235-239.

Freud, S. (1961). The resistances to psycho-analysis. In The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume XIX (1923-1925): The Ego and the Id and other works (pp. 211-224).

Greenwald, A. G., & Banaji, M. R. (1995). Implicit social cognition: attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological review, 102(1), 4.

Stroop, J. R. (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of experimental psychology, 18(6), 643.

Tulving, E. (1972). Episodic and semantic memory. In E. Tulving & W. Donaldson (Eds.), Organization of Memory, (pp. 381–403). New York: Academic Press.

How to reference this article:

How to reference this article:

McLeod, S. A. (2018, April 05). What are the most interesting ideas of Sigmund Freud? Simply Psychology. www.simplypsychology.org/Sigmund-Freud.html

Home

|

About Us

|

Privacy Policy

|

Advertise

|

Contact Us

Back to top

Simply Psychology’s content is for informational and educational purposes only. Our website is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment.

© Simply Scholar Ltd – All rights reserved