Patients who are having trouble coping with cancer may find it helpful to talk with a professional about their concerns and worries. These specialists may include the following:

Patients find it easier to adjust if they can carry on with their usual routines and work, keep doing activities that matter to them, and cope with the stress in their lives. Patients who adjust well to coping with cancer continue to find meaning and importance in their lives. Patients who do not adjust well may withdraw from relationships or situations and feel hopeless.

The way patients cope is usually linked to their personality traits (such as whether they usually expect the best versus the worst, or if they are shy versus outgoing).

Distress can occur when patients feel they are unable to manage or control changes caused by cancer. Patients with the same diagnosis or treatment can have different levels of distress. Patients have less distress when they feel the demands of the diagnosis and treatment are low or the amount of support they get is high. For example, a health care professional can help the patient adjust to the side effects of chemotherapy by giving medicine for nausea .

Cancer patients need different coping skills at different points in time.

Living with a diagnosis of cancer involves many life adjustments. Normal adjustment involves learning to cope with emotional distress and solve problems caused by having cancer.

The coping skills needed will change at different points in a patient’s cancer journey. These include the following:

- Hearing the diagnosis.

- Being treated for cancer.

- Finishing cancer treatment.

- Learning that the cancer is in remission.

- Learning that the cancer has come back.

- Deciding to stop cancer treatment.

- Becoming a cancer survivor.

Hearing the diagnosis

The process of adjusting to cancer begins before patients hear the diagnosis. Patients may feel worried and afraid when they have unexplained symptoms or are having tests done to find out if they have cancer.

A diagnosis of cancer can cause patients to have more distress when their fears become true. It may be difficult for patients to understand what the doctors are telling them during this time. For more information, see the Talking with the Health Care Team section in Communication in Cancer Care.

Additional help from health professionals for problems such as fatigue, trouble sleeping, and depression may be needed during this time.

Being treated for cancer

As patients go through cancer treatment, they use coping skills (also known as coping strategies) to adjust to the stress of treatment.

Patients who have comorbidities, a decreased ability to manage their daily routines, or a self-reported diagnosis of depression or back pain may be more likely to experience anxiety during chemotherapy treatment than those who do not.

Coping skills can help patients with certain problems, emotional distress, and cancer by using thoughts and behaviors to adjust to life situations. For example, changing a daily routine or work schedule to manage the side effects of cancer treatment is a coping skill.

Remission after treatment

Patients may be glad that treatment has ended but feel increased anxiety as they see their treatment team less often. Other concerns include returning to work and family life and being worried about any change in their health.

Many patients will feel increased distress after finishing treatment, but this usually does not last long and may go away within a few weeks.

During remission, patients may become distressed before follow-up medical visits because they worry that the cancer has come back. Waiting for test results can be very stressful.

Learning that the cancer has come back

Cancer that comes back after treatment may cause an increase in distress from having:

- A return of symptoms.

- A sense of hopelessness.

- A negative view of the cancer.

The patient’s quality of life may be improved if they are able to manage their cancer and have support from friends and family.

Stopping cancer treatment

Sometimes cancer comes back and does not get better with treatment. The treatment plan then changes from one that is meant to cure the cancer to one that gives comfort and relieves symptoms. This may cause the patient to have an increase in anxiety or depression. For more information, see Depression and Cancer-Related Post-traumatic Stress.

Patients who adjust to the return of cancer often keep up hope in meaningful life activities. Some patients look to spirituality or religious beliefs to help keep up their quality of life. For more information, see Spirituality in Cancer Care.

Becoming a long-term cancer survivor

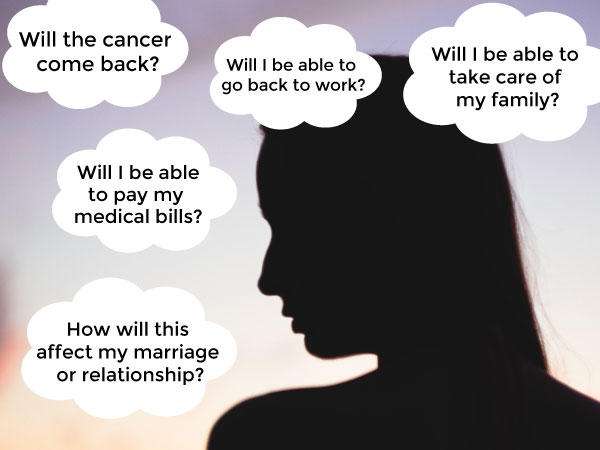

Patients adjust to finishing cancer treatment and being long-term cancer survivors over many years. Some common problems reported by cancer survivors as they face the future include the following:

- Feeling anxious that the cancer will come back.

- Feeling a loss of control.

- Having anxiety and nausea in response to reminders of chemotherapy (such as smells or sights).

- Having symptoms of post-traumatic stress, such as being unable to stop thinking about cancer or its treatment or feeling alone or separate from others.

- Feeling tired all of the time.

- Being concerned about body image and sexuality.

Regular exercise and individual or group counseling may help improve these problems and the patient’s quality of life.

Most patients adjust well and some even say that surviving cancer has given them a greater appreciation for life, a better understanding of what is most important in their life, and stronger spiritual or religious beliefs.

Some patients may have more trouble adjusting because of medical problems, fewer friends and family members who give support, money problems, or mental health problems not related to the cancer.

Overview

Anxiety is a normal reaction to cancer. One may experience anxiety while undergoing a cancer screening test, waiting for test results, receiving a diagnosis of cancer, undergoing cancer treatment, or anticipating a recurrence of cancer. Anxiety associated with cancer may increase feelings of pain, interfere with one’s ability to sleep, cause nausea and vomiting, and interfere with the patient’s (and their family’s) quality of life. If normal anxiety gives way to abnormally high distress, becomes incapacitating, or involves excessive fear or worry, it may warrant its own treatment. In that instance, If left untreated, anxiety may even be associated with lower survival rates from cancer.

Persons with cancer will find that their feelings of anxiety increase or decrease at different times. A patient may become more anxious as cancer spreads or treatment becomes more intense. The level of anxiety experienced by one person with cancer may differ from the anxiety experienced by another person. Most patients are able to reduce their anxiety by learning more about their cancer and the treatment they can expect to receive. For some patients, particularly those who have experienced episodes of intense anxiety before their cancer diagnosis, feelings of anxiety may become overwhelming and interfere with cancer treatment.

April 30, 2020, by NCI Staff

Studies have shown that anxiety and stress are common among long-term cancer survivors.

Credit: National Cancer Institute

Being diagnosed with cancer and going through intensive treatment is stressful. So, when treatment ends, family and friends are eager to celebrate. But many cancer survivors don’t feel like celebrating or don’t feel ready to move on with their lives.

One reason for this apparent disconnect is that “it can be scary to go from seeing [health care] providers and a medical team on a regular basis to not being seen as frequently,” said Suzanne Danhauer, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist at Wake Forest School of Medicine. As a result, Dr. Danhauer said, survivors’ distress levels often go up, often unexpectedly.

Fear that the cancer will come back, or recur, is another source of distress for many survivors. People often feel especially anxious when they’re due for a scan or other follow-up medical visit—a feeling that some cancer survivors have dubbed “scanxiety.”

“Scans are like revolving doors, emotional roulette wheels that spin us around for a few days and spit us out the other side,” wrote cancer survivor Bruce Feiler, in a June 2011 Time magazine article. “Land on red, we’re in for another trip to Cancerland; land on black, we have a few more months of freedom.”

“Fear of recurrence is the most common emotional difficulty that people tell us they have after they’ve completed [cancer] treatment,” said Karen Syrjala, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle. And while a certain amount of anxiety is normal, for some survivors it can become debilitating, she said.

Coronavirus Pandemic Adds to Anxiety and Stress for Cancer Patients, Survivors

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in new sources of anxiety and stress for many cancer patients and survivors. For several reasons, COVID-19 “has been a significant added burden” for patients with cancer, said clinical psychologist Shelley Johns, Psy.D., of the Regenstrief Institute and Indiana University.

Some cancer treatments may weaken the immune system, which may increase a person’s risk of severe illness from SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. In addition, Dr. Johns said, steps taken by hospitals and other health care organizations to deal with the pandemic “are delaying or affecting the manner in which some patients are receiving their scheduled cancer treatments, adding [to their] stress.”

General advice on coping with stress due to the pandemic, such as this guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, can be helpful for cancer survivors as well as for others, Dr. Johns said.

Research shows that anxiety and distress are more common in long-term cancer survivors than in their healthy peers with no history of cancer. In addition to the fear of recurrence, other sources of cancer-related distress for survivors include concerns about family and finances, changes in body image and sexuality, and the challenges of managing their long-term health needs.

These cancer-specific types of distress “may not fall into the classic description of anxiety or depression but are still disruptive to [a person’s] quality of life,” Dr. Syrjala said.

Numerous approaches have been shown to help cancer patients and survivors cope with cancer-related anxiety and distress. However, many studies of these methods have been done in large cancer centers, and one challenge that remains is how to implement existing approaches in real-world settings, such as community oncology or primary care practices, said Deborah Mayer, Ph.D., R.N., interim director of NCI’s Office of Cancer Survivorship.

Another limitation, Dr. Mayer said, is that many studies of approaches to help survivors cope with anxiety and distress, as well as with depression, have focused only on women who are breast cancer survivors. “We need to study people with other types of cancers as well,” she said.

Studies supported by NCI and others, however, are exploring new ways to support the psychological and emotional health needs of a diverse range of cancer survivors and how to tailor existing approaches to meet the needs of specific individuals or groups.

As the number of long-term cancer survivors continues to grow, oncologists and other providers who care for survivors have become more aware that their patients are at increased risk of anxiety and distress.

“Cancer survivors need the expertise of someone who knows cancer and understands what is ‘normal’ for a cancer survivor,” Dr. Syrjala said. It’s important to reassure survivors that some degree of anxiety and distress is very much normal and won’t increase their risk of dying or cause the cancer to come back, she added.

“And that’s a starting point for being able to say, ‘How do we then move on to help you manage [those feelings]?’”

Approaches that have been shown to be helpful for managing anxiety and distress in cancer survivors include a type of psychotherapy called cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based stress reduction, self-management, exercise, and—in some cases—antianxiety or antidepressant medications.

Support groups can also be helpful, but the logistics of organizing them can be challenging, Dr. Syrjala said. The growth of online support groups for survivors of diverse cancer types and treatments has made these resources accessible to far more people, she noted.

For adolescent and young adult cancer survivors, peer support through programs like First Descents, an outdoor adventure therapy program that has been shown to reduce symptoms of psychological distress, can be helpful, said Bradley Zebrack, Ph.D., M.S.W., M.P.H., of the University of Michigan School of Social Work.

Some approaches that help adult cancer survivors cope with distress, including cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness-based stress management, can also help adolescents and young adults.

But these younger survivors have unique needs because “their lives are interrupted at a time when there is a lot of rapid emotional and psychological growth,” Dr. Zebrack said. “Re-engagement in work, school, and relationships with friends will be much more challenging for them than for people diagnosed with cancer when they are older and in later stages of life.”

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Fear of Recurrence

One approach that could help cancer survivors cope with distress is a newer form of cognitive behavioral therapy called acceptance and commitment therapy, or ACT.

“ACT supports survivors in figuring out what they can change by taking specific actions consistent with their values, yet recognizing the parts of their experience they can’t change,” explained clinical psychologist Shelley Johns, Psy.D., of the Regenstrief Institute and the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center.

For instance, she said, cancer survivors may always have concerns that the cancer will come back, but ACT can teach skills that help them “live with greater ease with those unchangeable realities.”

In a recent pilot study, Dr. Johns and her colleagues tested whether ACT could help breast cancer survivors better manage their fears of recurrence. Women in the study were randomly assigned to receive either 6 weeks of group-based ACT, a six-session survivorship education workshop, or a 30-minute group coaching session with a booklet on life after cancer treatment.

Six months after the intervention, participants in the ACT group reported greater reductions in the severity of their fear of recurrence than women in the other two groups. ACT also reduced anxiety and symptoms of depression at the 6-month follow-up point and improved survivors’ quality of life more than the other interventions, Dr. Johns said.

With ACT, she continued, “we offer coping skills so that fear is no longer ‘driving the car’ in survivors’ lives. The fear may still be in the car, yet it can ride in the back seat, while survivors keep their hands on the wheel and drive in their preferred direction.” These skills include pursuing meaningful activities, focusing on the present moment (mindfulness), and being kinder to yourself.

Storytelling to Help Survivors and Caregivers Cope with Distress

Addressing the needs of caregivers is another important area of research, Dr. Mayer said, as studies show that spouses and partners of cancer survivors are also more prone to anxiety than other people and may have their own health issues.

Health communication and behavioral scientist Wonsun (Sunny) Kim, Ph.D., of Arizona State University Edson College of Nursing and Health Innovation, is studying the effectiveness of a 4-week web-based digital storytelling approach to help both patients with cancer undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) and their caregivers.

In an ongoing clinical trial, her team is investigating whether viewing personal, emotionally engaging “digital stories” told by other HSCT survivors and their caregivers during a 3-day digital storytelling workshop can help them cope with psychosocial distress, such as depression, anxiety, and social isolation.

“We encourage patients and caregivers to watch the digital stories together and discuss not just the story itself but also the emotions they felt” while watching, Dr. Kim said. Study participants are being followed for 3 months to learn whether the series of stories helps them talk with loved ones about how they are feeling, and thereby improve their emotional well-being. Patients and caregivers may not talk to each other about feelings such as anxiety “because they don’t want to worry the other person,” Dr. Kim noted.

If the approach is successful, she hopes to do a longer follow-up study to examine the effectiveness of the narrative-based digital storytelling approach for optimizing patient and caregiver psychosocial well-being during and after a transplant.

Additionally, she said, “The storytelling approach has broad applicability to other cancer types and other points in the cancer journey, depending on how we design the storytelling workshop” where the videos are made.

Exercising Together for Better Mental Health

At Oregon Health and Science University’s Knight Cancer Institute, exercise scientist Kerri Winters-Stone, Ph.D., is studying the effects of partnered exercise training on the physical and mental health and relationship quality of couples (survivors and their partners) coping with cancer.

“Cancer affects each partner’s physical and mental health and puts a strain on their relationship. It’s like a triple threat,” Dr. Winters-Stone said in a video being used to recruit study participants.

The Exercising Together trial is designed to learn whether and how exercise can benefit prostate, breast, or colorectal cancer survivors and their partners. Participants will be randomly assigned to exercise twice a week for 6 months in one of three groups: partnered exercise classes in a group setting, separate survivor and partner exercise classes in a group setting, or home-based, unsupervised, separate exercise for survivors and their partners.

The study will examine whether exercising together helps to reduce participating couples’ anxiety, depression, and fear of recurrence and improve their physical health and the quality of their relationship.

“If couples train together as a team during exercise, we hope this can transfer outside of the gym and help them function better as a team in all facets of their life,” Dr. Winters-Stone said.

Her long-term goal is to make a compelling case that exercise should be included as a standard of care for every person with cancer. “We want partners to be included, too, because we know they’re also affected by cancer,” she said. “And that by keeping couples healthy, we achieve the best outcomes for everyone.”

Adjusting Research During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The pandemic is also affecting cancer survivors participating in some clinical trials. For example, Kerri Winters-Stone, Ph.D., said that major changes had to be made to two NCI-funded clinical trials she was leading of exercise training to improve the physical and mental health of survivors.

“We had to transfer all of our supervised, group-based exercise classes to video conference group exercise with just a few days’ notice,” Dr. Winters-Stone said. “We thought it was important to keep our participants physically active under these very difficult times that are causing high anxiety and distress for everyone, and more so for people with cancer. We also wanted to keep their exercise group together, so we use a group video interface and let them socialize before and after online class.”

Telehealth for Cancer Survivors in Rural Areas

Helping cancer survivors who live in rural areas cope with cancer-related anxiety and distress can be especially challenging. Survivors in these areas live far from large cancer centers, and “there often aren’t health providers in rural areas, especially mental health providers, who have oncology experience,” Dr. Danhauer said.

That’s where researchers hope that “telehealth” approaches such as therapy and other psychosocial support delivered by phone, mobile apps, and websites may be useful.

Dr. Danhauer and another clinical psychologist at Wake Forest, Gretchen Brenes, Ph.D., are conducting a pilot study that uses a cognitive behavioral therapy workbook as part of a stepped-care approach (based on the severity of symptoms) to help adult cancer survivors in rural areas who have clinically significant symptoms of anxiety or depression.

If randomly assigned to the stepped-care group, “people with more severe depression or anxiety will receive the workbook and work through it with a therapist on the telephone,” Dr. Danhauer said. Survivors with lower levels of depression or anxiety will go through the workbook on their own and check in with a research team member by phone every couple of weeks. Participants in the control group will receive information about resources, including local mental health providers.

If the pilot study results are promising, “we want to do a larger study looking at a telephone-based cognitive behavioral therapy intervention for distress in cancer survivors,” Dr. Danhauer continued.

She and Dr. Brenes also have a pilot research grant from Wake Forest Baptist Comprehensive Cancer Center to adapt the workbook and the telehealth approach linguistically and culturally for Hispanic cancer survivors.

Providing Resources When and Where People Need Them

The studies described here are just a sample of ongoing research to help cancer survivors cope with anxiety and distress, according to Ashley Wilder Smith, Ph.D., M.P.H., chief of NCI’s Outcomes Research Branch. “Cancer is many diseases and has many different trajectories, and researchers are exploring lots of ways to support cancer patients and survivors as they go through this experience,” Dr. Smith said.

Other examples of NCI-funded studies include a randomized trial of a self-management handbook, with or without telephone counseling, for improving psychological distress and other measures in an ethnically diverse group of cancer survivors and their informal caregivers, and a study of culturally adapted cognitive behavioral stress management and self-management for Hispanic prostate cancer survivors.

One challenge that remains, Dr. Syrjala said, is that “we need to have the systems in place to make resources available when and where people need them, especially after patients finish treatment.”

To help address this challenge, NCI’s IMPACT Consortium, an initiative funded through the Cancer MoonshotSM, is looking at ways to incorporate the management of symptoms, including psychological symptoms, into electronic health records. This will allow such symptoms to be addressed in a more routine and comprehensive fashion in people with cancer and cancer survivors, Dr. Smith noted.

Finding the Silver Lining

Left unaddressed, serious anxiety, depression, or other types of psychological distress may leave cancer survivors unable to tend to their health care needs, Dr. Syrjala and other experts said. People may stop following treatment recommendations or avoid going to recommended follow-up appointments.

But surviving cancer can also lead to positive changes in a person’s life.

The flip side of psychological distress in survivors is “post-traumatic growth,” Dr. Syrjala said. The cancer experience may help survivors develop new strategies to manage emotional challenges, deepen their relationships with family or friends, and help them realize they have the strength to get through difficult situations. Surviving cancer may also lead people to re-evaluate their priorities and appreciate life more fully.

In addition, Dr. Smith said, “Cancer survivors may choose more healthy behaviors, such as exercising more or quitting smoking, because they are interested in a healthier life overall.”