Our articles are not designed to replace medical advice. If you have an injury we recommend seeing a qualified health professional. To book an appointment with Tom Goom (AKA ‘The Running Physio’) visit our clinic page. We offer both in person assessments and online consultations.

It’s easy to talk generally with rehab, ‘strengthen x,y and z’, improve movement control etc but we don’t often expand on what exactly this means. Today’s blog is a brief look at an exercise programme I used recently for a patient with Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome and what my thinking was behind it.

The patient, in this case, is a young male middle-distance runner called Ben. He is, at this stage, pain free with all daily activities and running up to 40 minutes with no symptoms. He’s progressed nicely from the initial session where even jogging on the spot was painful, however, longer runs over 45 minutes cause some discomfort in the medial tibia. This has been a recurrent issue and Ben’s aim is to return to full training without these symptoms. He is gradually re-introducing high intensity sessions with guidance from his running coach and managing well. Assessment reveals mild weakness in Soleus, Glute Med and the posterior chain. Control of single leg balance and single leg dip is good and equal left and right. Ben works with an S&C Coach and is in the gym 3 days per week and is keen to have a number of exercises to work on.

Broadly speaking our aims are as follows:

- Improve local load capacity in the calf complex

- Improve kinetic chain load capacity considering the key muscles that aid in managing load

- Include weight-bearing exercises to improve bone load capacity

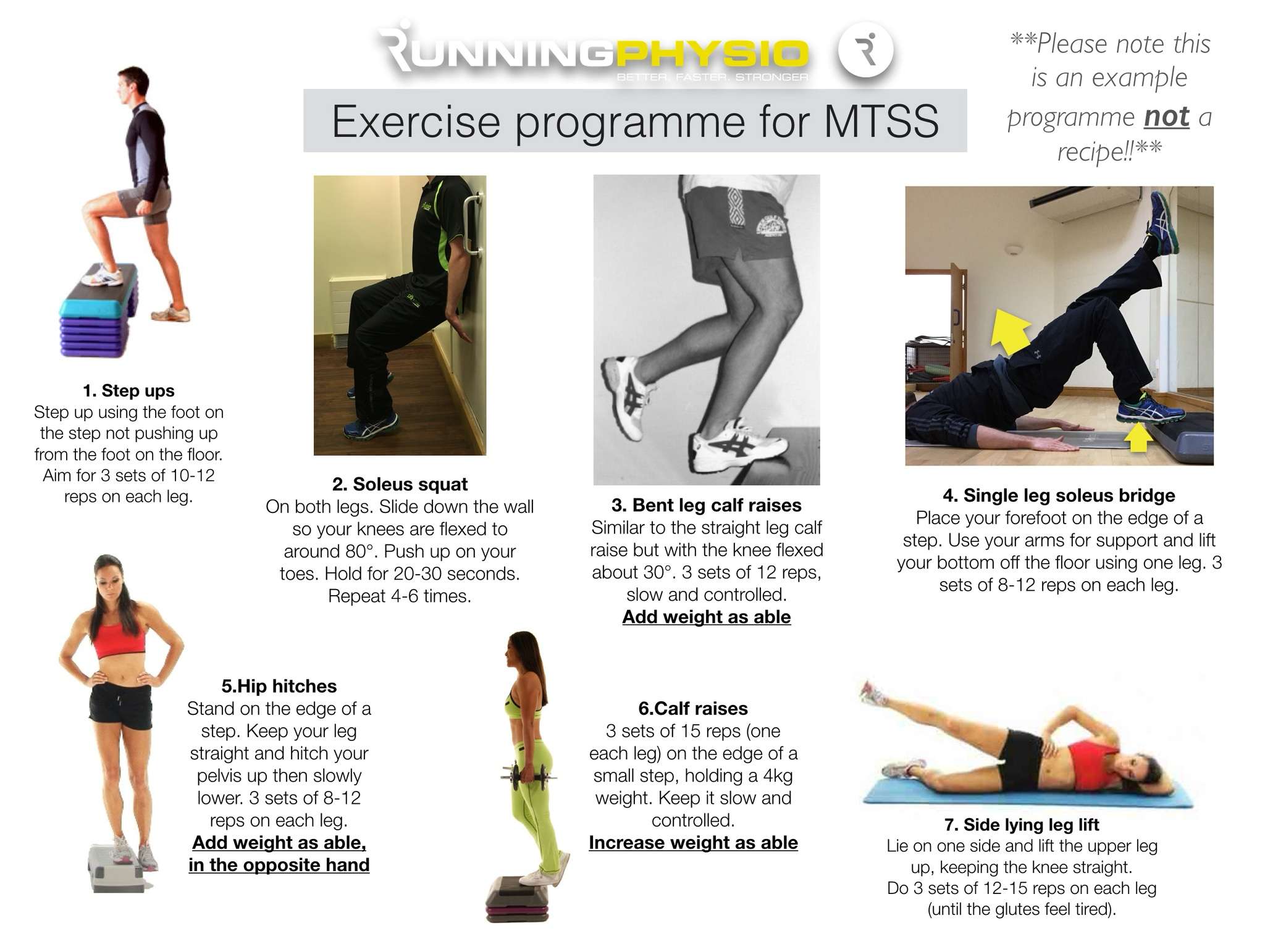

So Ben’s programme looks like this:

Let’s walk through each exercise.

1. Step ups

Simple but very effective! Step-ups achieve high levels of Glute Max activity (Reiman et al. 2012) as well as working Glute Med and providing a proprioceptive challenge. Gluteal muscles are vital in absorbing load during the stance phase of running. This exercise is first due to control aspect; doing this once fatigued from the other exercises may compromise movement quality. It is easy to progress or adapt to suit the patients changing needs.

2. Soleus squat

A nice isometric option that will challenge both the Soleus and Quads – 2 vital muscles in absorbing load during running. Hamner et al. (2010) found the quadriceps to be the greatest contributor to support.

3. Bent leg calf raise

A significant challenge to the calf complex especially Soleus. In MTSS Soleus is thought to be particularly important as it helps to reduce the bending force that the tibia experiences during impact which is thought to be key to the development of bone stress injury (Warden et al. 2014).

4. Single leg soleus bridge

Note this bridge is done with the forefoot on the edge of a step. The aim is 1) to lengthen the lever to challenge the posterior chain and 2) to work the soleus (again!). The soleus load may be fairly low but this will challenge Glute Max and the hamstrings. The hamstrings are most active during swing phase but they also contribute to the loading phase through co-contraction with the quads.

5. Hip hitches (AKA ‘Pelvic Drop’)

Ben’s assessment revealed Glute Med weakness and this is hoping to address this. EMG studies suggest high levels of Glute Med activity and we can use this emphasize a ‘high free hip’ to help reduce pelvic drop during loading. Adding load in the opposite hand is a simple progression.

6. Straight leg calf raises

These will strengthen gastroc and soleus. As indicated above a strong calf complex is important in reducing bone load in MTSS. Ben is a forefoot striker and research indicates higher loads for the calf complex in this group (Almonroeder et al. 2013). We want to ensure he has adequate strength to manage this load.

7. Side lying leg lift

This old chestnut works Glute Med with minimal anterior hip flexor activity (McBeth et al. 2012). It’s a fairly simple exercise for isolated Glute Med strengthening. We’ve worked the glutes in an exercise where hip and knee control is included (step up) and where pelvic movement is controlled (the hip hitch), now we’re isolating it and trying to work to fatigue to stimulate strength gains. I include this at the very end as once you’ve worked the glutes to fatigue it makes control of other exercises very challenging!

We’ve given Ben some indication of reps and sets but also suggested he works to fatigue within each set. The rep range is currently roughly 8 to 15 reps. We’re using fatigue here as a method to ensure he’s loading enough. If Ben isn’t reaching fatigue within this range he needs to make the exercise harder by adding load, increasing range or increasing time under tension. We’ve also suggested Ben works alternate legs – work to fatigue on the right then exercise the left leg while the right leg recovers.

Communication is important here – Ben is happy with his exercises and how to progress each of them. We’ve also discussed them with his S&C coach and kept his running coach up to speed on his progress and load tolerance so we can work together as an integrated team.

As I’ve mentioned in the exercise image above this is not a recipe for MTSS just a snapshot of one patient’s exercises and why we’ve used them. Ben’s rehab is reviewed, adapted and progressed at each session and is part of a comprehensive management programme including athlete education, gait re-training and a graded return to running.

I don’t think there’s a right way and a wrong way to prescribe exercises but it’s good to have a reasoning process and be open to feedback. I asked a good friend of mine, Sam Blanchard (@SJBPhysio_Sport) for his views on the programme. Sam is Head of Rehab Physiotherapy for Rochester Amerks, has an excellent blog and has published some great research on exercise selection and progression. He raised 3 key points;

- You don’t necessarily have to work to fatigue to get stronger and you’d want to consider the impact of working to fatigue on his running and other training sessions. When managing concurrent training evidence suggests not working to failure may be preferable for performance gains. It’s worth noting, however, the majority of this research is in healthy individuals, without injury.

- Muscle fatigue is thought to be a key factor in the development of bone stress injury. You may want to work proprioception or strengthen the glutes in a fatigued state which may simulate loading characteristics during longer runs.

- Impact work could be added as a progression to improve bone load capacity and active stiffness in the calf complex

Sam makes some great points and I agree, in particular, it is important to strike a balance between rehab and running. We’ve worked with Ben’s S&C and Running Coaches to develop a programme that allows adequate recovery between strength and running sessions. In addition, Ben has recently added low-level plyometric work to his rehab programme with an emphasis on controlled, comfortable impact. Sam was right on the money there!

Closing thoughts: exercise prescription for MTSS and other injuries requires an individualised approach considering how, when and where the athlete might do their rehab. It’s essential too that they know why they’re doing it and how it will help them achieve their goals. Not every patient will want an extensive programme; in fact, in many cases, 3 or 4 key exercises can be very effective. If you prescribe exercises try doing one of the programmes you’ve provided for a week – it’s much harder than you’d think! My final point is key…

…exercise prescription is all about reasoning, not recipes!

If you’d like to share an example of exercises you’ve used for a runner and your reasoning behind them please email your ideas to me, [email protected] and we’ll feature the best ones on the site!

Pain generally in the inner and lower 2/3rds of tibia.

Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome (MTSS) is a common overuse injury of the lower extremity. It typically occurs in runners and other athletes that are exposed to intensive weight-bearing activities such as jumpers[1]. It presents as exercise-induced pain over the anterior tibia and is an early stress injury in the continuum of tibial stress fractures.[2].

It has the layman’s moniker of “shin splints.”[2]

Risk factor- quick increase in running volume

The incidence of MTSS ranges between 13.6% to 20% in runners and up to 35% in military recruits. In dancers it is present in 20% of the population and up to 35% of the new recruits of runners and dancers will develop it.[3]

Large increase in load, volume and high impact exercise can put at risk individuals to MTSS. Risk factors include being a female, previous history of MTSS, high BMI, navicular drop, reduced hip external rotation range of motion, muscle imbalance and inflexibility of the triceps surae), muscle weakness of the triceps surae (prone to muscle fatigue leading to altered running mechanics, and strain on the tibia), running on a hard or uneven surface and bad running shoes [2][4] [5]

Periosteum, vivid green

The pathophysiologic process resulting in MTSS is related to unrepaired microdamage accumulation in the cortical bone of the distal tibia, however this has not been definitively established. Two current theories are:

- The pain is secondary to inflammation of the periosteum as a result of excessive traction of the tibialis posterior or soleus, supported by bone scintigraphy findings of a broad linear band of increased uptake along the medial tibial periosteum. But a case-controlled ultrasound based study which compared periosteal and tendinous edema of athletes with and without medial tibial stress syndrome found no difference between the groups.

- Bony overload injury, with resultant microdamage and targeted remodeling. A study evaluating tibia biopsy specimens from the painful area of six athletes suffering from medial tibial stress syndrome gave only equivocal support for this theory. Linear microcracks were found in only three specimens and there was no associated repair reaction[6].

Clinical Presentation and Assessment

[

edit

|

edit source

]

KEY POINTS FOR ASSESSMENT MTSS[3]HISTORY

- Increasing pain during exercise related to the medial tibial border in the middle and lower third

- Pain persists for hours or days after cessation of activity

- Pain decreases with running (early stage)

- Differentiate from exertional compartment syndrome, for which pain increases with running

- Earlier onset of pain with more frequent training (later stages)

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

- Intensive tenderness of the involved medial tibial border, more than 5 cm

- Pes planus

- Tight Achilles tendon

- A “one-leg hop test” is a functional test, that can be used to distinguish between medial tibial stress syndrome and a stress fracture: a patient with medial tibial stress syndrome can hop at least 10 times on the affected leg where a patient with a stress fracture cannot hop without severe pain. The sensitivity of the hop test for diagnosing medial tibial stress fracture when pain and tenderness were present was 100%, the specificity 45%, the positive predictive value 74%, and the negative predictive value 100%

- Provocative test: pain on resisted plantar flexion

IMAGINGMRI: Periosteal reaction and edemaTREATMENTSee later in page

[7][8][4][3][6]

Watch this video on MTSS.

Navicular drop test

Management of MTSS is conservative, focusing on rest and activity modification with less repetitive, load-bearing exercise. No specific recommendations on the duration of rest required for resolution of symptoms, and it is likely variable depending on the individual.

Other therapies available (with low-quality evidence) include iontophoresis, phonophoresis, ice massage, ultrasound therapy, periosteal pecking, and extracorporeal shockwave therapy. A recent study on naval recruits showed prefabricated Introduction to Orthotics reduced MTSS[2].

Complications: Recurrence common after resumption of heavy activity.[9]

Physical Therapy Management

[

edit

|

edit source

]

Patient education and a graded loading exposure program seem the most logical treatments.[7] Conservative therapy should initially aim to correct functional gait, and biomechanical overload factors.[3]Recently ‘running retraining’ has been advocated as a promising treatment strategy and graded running programme has been suggested as a gradual tissue-loading intervention.[3]

Prevention of MTSS was investigated in few studies and shock-absorbing insoles, pronation control insoles, and graduated running programs were advocated.[3]

Over-stress avoidance is the main preventive measure of MTSS or shin-splints. The main goals of shin-splints treatment are pain relieve and return to pain‑free activities.[10]

Acute phase

[

edit

|

edit source

]

2-6 weeks of rest combined with medication is recommended to improve the symptoms and for a quick and safe return after a period of rest. NSAIDs and Acetaminophen are often used for analgesia. Also cryotherapy with Ice-packs and eventually analgesic gels can be used after exercise for a period of 20 minutes.

- There are a number of physical therapy modalities to use in the acute phase but there is no proof that these therapies such as ultrasound, soft tissue mobilization, electrical stimulation[11] would be effective.[4] A corticoid injection is contraindicated because this can give a worse sense of health. Because the healthy tissue is also treated. A corticoid injection is given to reduce the pain, but only in connection with rest.[5]

- Prolonged rest is not ideal for an athlete.

Subacute phase

[

edit

|

edit source

]

The treatment should aim to modify training conditions and to address eventual biomechanical abnormalities. Change of training conditions could be decreased running distance, intensity and frequency and intensity by 50%. It is advised to avoid hills and uneven surfaces.

- During the rehabilitation period the patient can do low impact and cross-training exercises (like running on a hydro-gym machine). After a few weeks athletes may slowly increase training intensity and duration and add sport-specific activities, and hill running to their rehabilitation program as long as they remain pain-free.

- A stretching and strengthening (eccentric) calf exercise program can be introduced to prevent muscle fatigue. [12][13][14] Patients may also benefit from strengthening core hip muscles. Developing core stability with strong abdominal, gluteal, and hip muscles can improve running mechanics and prevent lower-extremity overuse injuries. [14]

- Proprioceptive balance training is crucial in neuromuscular education. This can be done with a one-legged stand or balance board. Improved proprioception will increase the efficiency of joint and postural-stabilizing muscles and help the body react to running surface incongruities, also key in preventing re-injury.[14]

- Choosing good shoes with good shock absorption can help to prevent a new or re-injury. Therefore it is important to change the athlete’s shoes every 250-500 miles, a distance at which most shoes lose up to 40% of their shock-absorbing capabilities.

In case of biomechanical problems of the foot, individuals may benefit from Introduction to Orthotics. An over-the-counter orthosis (flexible or semi-rigid) can help with excessive foot pronation and pes planus. A cast or a pneumatic brace can be necessary in severe cases.[4] - Manual therapy can be used to control several biomechanical abnormalities of the spine, sacro-illiacal joint and various muscle imbalances. They are often used to prevent relapsing to the old injury.

- There is also acupuncture, ultrasound therapy injections and extracorporeal shock-wave therapy but their efficiency is not yet proved.

Differential Diagnosis

[

edit

|

edit source

]

ConditionCharacteristicsTissue originAnterior tibial stress syndromeVague, diffuse pain along anterolateral tibia, worse at beginning of exercise that decreases during trainingPeriosteumMedial tibial stress syndromeVague, diffuse pain along middle-distal tibia, worse at beginning of exercise, that decreases during trainingTibial/fibular stress fracturePain with running, point tenderness over fracture site, “dreaded black line” on lateral x-rayBoneExertional compartment syndromeSymptoms begin 10min into exercise andresolve 30min after exercise, sensory or motor loss, elevated anterior compartment pressuresMuscle and fasciaLeg TendinopathyMay be Achilles tendon, peroneal tendon, or tibialis posteriorTendonSural or SPN entrapmentDermatomal distribution of symptomsNerveLumbar radiculopathyWorse with lumbar tension position (sitting)Popliteal artery entrapmentDiagnosed with vascular studiesBlood vessel

[9]

Clinical Bottom Line

[

edit

|

edit source

]

‘Shin splints’ is a vague term that implicates pain and discomfort in the lower leg, caused by repetitive loading stress. There can be all sorts of causes to this pathology according to different researches. Therefore, a good knowledge of the anatomy is always important, but it’s also important you know the other disorders of the lower leg to rule out other possibilities, which makes it easier to understand what’s going wrong. Also a detailed screening of known’s risk factors, intrinsic as well as extrinsic, to recognize factors that could add to the cause of the condition and address these problems.