Long-term reactions to trauma are unique, personal, and often painful. Sometimes the reactions seem random, as if they have little to do with the trauma. Other times, they are simply too much. They are vivid, painful, and overwhelming. A step in many trauma interventions involves normalizing these reactions, and showing that a person is not broken, wrong, or alone.

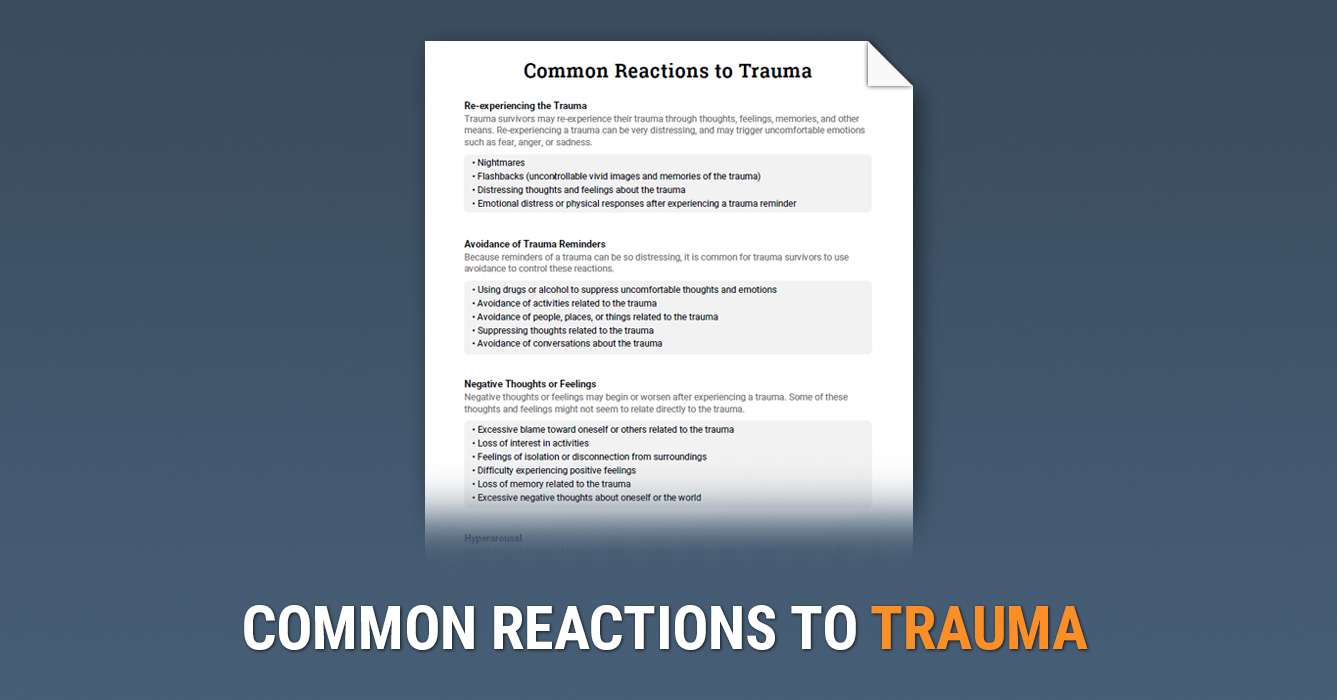

The Common Reactions to Trauma worksheet summarizes the common symptoms and reactions that many people experience after a trauma. The goal of this tool is to validate and normalize a range of reactions to trauma, which can have numerous benefits. Symptoms that may have seemed random and uncontrollable are now attached to a trauma, building hope that they may be treated.

This tool is best used as a prompt for discussion about an individual’s unique response to trauma. Encourage your client to describe the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors they have experienced since the trauma, using this resource as a roadmap.

Trauma is complicated. It can be obvious, with a clear cause, and symptoms that seem to make sense. Or, trauma can be buried beneath depression, anxiety, and anger, without any recognizable origin. The causal event may have occurred a week ago, or half a century in the past.

To help survivors of trauma make sense of what they’re experiencing, psychoeducation is a natural place to begin. Psychoeducation can help by normalizing the experience of trauma, and by giving a name to the enemy. It can help your clients build the confidence they need to know they can get better.

Our What is Trauma? info sheet offers a basic overview of trauma, including a definition, information about risk factors, symptoms, and common treatments. This printout was designed to be used with new clients and their families as an introduction to trauma.

Trauma Narratives

Most adults have at least a few memories that are downright painful. On the lighter end, there are those embarrassing experiences that cause you to cringe, even decades later. Then, there’s heavier stuff, like heartbreak, loss, and regret. These memories are more than a series of facts and images—they also carry powerful emotions that feel like a punch to the gut every time they surface.

In the case of trauma, this phenomenon is taken to the extreme. Traumatic memories are so emotionally loaded that even the smallest of reminders can be crippling. The sound of a car horn might trigger a panic attack, or a familiar smell can lead to an uncontrollable rage.

Naturally, many survivors of trauma do their best to avoid these memories—who would willingly expose themselves to even more pain? Unfortunately, avoidance of trauma can sometimes be more harmful than it is helpful. Avoidance can cause trauma can become more painful, and some triggers are simply impossible to avoid.

One way that therapists help survivors of trauma is through exposure treatments. During exposure, a client will be confronted with reminders of their trauma gradually, in a safe environment. With enough exposure, memories of trauma lose their emotional power.

In this guide, we’ll be exploring a single exposure technique called the trauma narrative. The trauma narrative is a powerful technique that allows survivors of trauma to confront and overcome their painful memories through storytelling.

What is a Trauma Narrative?

The trauma narrative is a psychological technique used to help survivors of trauma make sense of their experiences, while also acting as a form of exposure to painful memories.

Without treatment, the memories of a trauma can feel like a jumbled mess—an unbearable wash of images, sounds, and emotions. When completing a trauma narrative, the story of a traumatic experience will be told repeatedly through verbal, written, or artistic means. Sharing and expanding upon a trauma narrative allows the individual to organize their memories, making them more manageable, and diminishing the painful emotions they carry.

Trauma stories are often shared organically through conversation, both in and out of treatment. Sometimes, the organic retelling of a traumatic experience can be disruptive, especially if it’s in an inappropriate setting (e.g. work or school). Learning to use trauma narratives purposefully with your clients allow you to control for these potential problems.

How to Use Trauma Narratives

Psychoeducation

As with any form of exposure therapy, psychoeducation should always come first. It’s important that your client understands the basics of trauma, the importance of treating trauma (as opposed to avoiding it), and how exposure therapy works.

A comprehensive overview of trauma psychoeducation is beyond the scope of this guide, but some key points include:

- Trauma is a normal reaction to many experiences, and the way each person handles it is unique.

- Avoiding reminders of a trauma might feel good in the moment, but it will cause symptoms to be worse when they do arise.

- After enough exposure to traumatic memories, their potency will diminish.

- It’s normal to feel uncomfortable when discussing trauma. Reassure your client that they will never be in danger, and if it feels too bad, they can always stop.

Creating the Narrative

Most trauma narratives will require several sessions to be completed. The speed at which you and your client progress will be determined by their comfort level, the amount of detail shared, and your clinical judgment.

Tip:

Trauma narratives can be emotionally draining, especially when exploring new territory. Be sure to leave plenty of time before the end of a session for your client to decompress and regain composure.

Start with the Facts

Your client’s first retelling of their trauma story should focus on the facts of what happened. Encourage them to share the who, what, when, and where of their traumatic experience. Thoughts and feelings will come in later.

Trauma narratives are most effective when they’re written. However, for many people, it will be difficult to get started with a completely blank canvas. In these cases, talking through the facts will make it easier to write them down later.

If the facts are too difficult to get out, break things down further. Ask your client to write separate entries about what happened before, during, and after their trauma.

Tip:

Younger children can complete trauma narratives by drawing, painting, or playing instead of writing. For example, allow them to act out their memories with action figures or dolls.

Adding Thoughts and Feelings

After writing about the facts of a trauma, it’s time for your client to revise and add more detail. Ask them to slowly read through their narrative, adding information about the thoughts and feelings they experienced during their trauma. Revisions to the facts are also acceptable during this part of the process.

Your role as the helper is to encourage more sharing. Avoid challenging any irrational thoughts, for now. Instead, use open questions to help your client explore their thoughts and feelings in key areas. Don’t worry about digging down too deep in any one area—that’ll come next.

Digging Deeper

As your client becomes more comfortable telling their story, you’ll begin to focus on the more uncomfortable parts of their experience. Ask your client to share their worst memory, or the worst moments, of their trauma. Dig deeper in this area by adding as much detail as possible to the narrative.

If this section is difficult for your client, it’s OK to move slowly. Spend time reviewing what has already been written, and allow more details to be added gradually. Try prompting your client by asking about each of their senses, and what they were thinking and feeling during the worst moments of the trauma.

Wrapping Up

Now that your client’s narrative has been read and re-read in detail, and it has become somewhat easier for them to discuss, cognitive skills can be used. Review the story once again, this time challenging any irrational thoughts. Allow your client to revise any sections as they see fit.

Finally, ask your client to write one last paragraph about how they feel differently now, as opposed to when their trauma was occurring. What have they learned? Have they grown stronger in any ways? What would they say to someone else who was going through the same experience?

Multiple Traumas

In some cases, your client may have experienced multiple traumatic incidents, such as in a long abusive relationship, or exposure to war over many months. Allow your client to determine what’s included in their trauma narrative, and what isn’t.

Instead of a single trauma narrative, some might choose to write a “life narrative”, or something closer to a timeline of incidents. Another option is to create a timeline as an overarching guideline, and then honing in on one particular experience.

The Helper’s Role

- The sharing of a trauma can be immensely difficult due to feelings of shame, fear, and embarrassment. Focus on your core listening skills such as reflections, open questions, and empathy.

- Do your best to not interrupt, as long as your client is on track. If your client does get off track, ask for more detail about a particular part of their story using open questions.

- Helpers are people too, and sometimes, you might feel bad pushing your client in a difficult direction. It’s a normal instinct to feel empathy, and not want to “hurt” the person sitting in front of you. However, this behavior can feed into avoidance. Check your own feelings throughout the narrative to avoid this trap.

- Frequently ask your client to read what they’ve written out loud, even if it starts to feel repetitive. This is part of the exposure process.

Example Trauma Narrative

First Draft: The Facts

It was a Sunday morning and I was planning on visiting my family. Before that I ate breakfast and went to the gym, like I always do on Sunday mornings. I talked to my mom on the phone, then left the house at about 10:30 AM to drive across town to my parents’ house.

Around 11 AM I was driving down Roosevelt Boulevard when a gold car turned right in front of me. I slammed on my brakes, but couldn’t stop in time. I hit their passenger side door. My car flipped, and I think the other person’s car was all smashed up. I was stuck in the car for a long time. I could hardly move, and I remember glass was everywhere. My body was numb. When help arrived they ripped open the car and pulled me out. Everything is a blur, but there were flashing lights and people watching.

After I got out of the car they took me to the hospital in an ambulance. I could hear loud sirens the whole way, but I can’t remember much else about the ambulance ride. The doctors told me I blacked out. I ended up staying in the hospital for a long time, a few weeks. I had a bunch of broken bones, and I had lost a lot of blood.

Second Draft: Thoughts and Feelings

It was a Sunday morning and I was planning on visiting my parents. I was in a good mood because I had just finished my finals at my university the day before, and new classes weren’t starting for 3 weeks.

Before leaving I ate breakfast and went to the gym, like I always do on Sunday mornings. I talked to my mom on the phone, then left the house at about 10:30 AM to drive across town to my parent’s house.

Around 11 AM I was driving down Roosevelt Boulevard when a gold car turned right in front of me. I remember my heart skipping a beat and my whole body locking up. I didn’t have time to think, I just slammed my brakes. I couldn’t stop in time, and I hit their passenger side door. My car flipped, and I think the other person’s car was all smashed up.

I was stuck in the car for a long time. I was so scared, I thought I was going to die. For a little while, I actually thought I was dead. I could hardly move, and I remember glass was everywhere. My body was numb, and I was struggling just to breathe. I could see my own blood. When help arrived they ripped open my car and pulled me out. I remember how bright it was outside. Everything was a blur, but there were flashing lights from a firetruck, and people were watching. They put me on a stretcher and rushed me into an ambulance.

I can’t remember much else about the ambulance ride. The doctors told me I blacked out. I ended up staying in the hospital for a long time—a few weeks. I had a bunch of broken bones, and I had lost a lot of blood. For a long time I still thought I would die. After I got a little bit better, I still thought I could lose my legs. They told me it would take a long time before I would be able to walk again, and I thought “I’ll never be able to live a normal life”. I was so scared for such a long time.

Now I’m getting better—I’m going to physical therapy to rebuild the strength in my legs. I’m still very afraid of cars, even if I just think about them. When I think back to my accident I feel like I’m starting to have a panic attack, so I try to think of something else. I can’t imagine ever being comfortable in a car again, let alone driving myself.

Final Draft: The Worst Moments, Conclusions

Note:

In the final draft, most changes will be made to the “worst moment” of the trauma, and the closing paragraphs. In this excerpt, we’ll focus on those areas.

The Worst Moments

I was stuck in the car for a long time… maybe 30 minutes. This was the worst part of the whole experience. I was so scared, I thought I was going to die. For a little while, I actually thought I was dead. I could hardly move, and I remember glass was everywhere. I had never felt so alone and helpless. I kept thinking about my family, and how they were still waiting for me to arrive. What would they think when I didn’t show up? My body was numb, and I was struggling just to breathe. I could see my own blood. When help arrived they ripped open my car and pulled me out. I kept thinking the EMTs were grimacing when they looked at me, but now I don’t know if they really were. They might have have just been concentrating on trying to help me.

Next, I remember how bright it was outside. Everything was a blur, but there were flashing lights from a firetruck, and people were watching. I was wondering if my parents were there, were they watching? I was thinking about how the accident was probably my fault, and people would be mad at me. The EMTs took me straight to an ambulance, which made me think something must be really wrong, because they were in such a rush.

The Closing Paragraph

Now I’m getting better—I’m going to physical therapy to rebuild the strength in my legs. I’m still very afraid of cars, but I believe I can get better. Now I’m able to tell my story without having a panic attack, and next I want to start working on getting back into a car. I realize that I was so scared I was going to die, but now I’ve made it. Even though my fear was so real, it’s in the past now, and it can’t hurt me. I want to focus on moving forward.

Trauma narratives are typically used within the context of a broader treatment. If you’re interested in learning more, we suggest taking some time to learn about Trauma Focused CBT and Narrative Exposure Therapy.

References

1. Cohen, J. A., & Mannarino, A. P. (2008). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapy for children and parents. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 13(4), 158-162.

2. Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., Cohen, J. A., Runyon, M. K., & Steer, R. A. (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children: impact of the trauma narrative and treatment length. Depression and anxiety, 28(1), 67-75.

3. Trauma Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A 12 Hour Workshop Covering Basic TF-CBT Theory, Components, Skills, and Resources (2013). Workbook with no publishing info.