Content warning: this piece contains a discussion of trauma due to sexual abuse and an account of child sexual abuse. Click here to go back to homepage

If you were to hear the term hypersexuality, what would you think it meant? An increased libido, or maybe an addiction to sex? These are easy assumptions to make — after all, according to Wikipedia, hypersexuality is “extremely frequent or suddenly increased libido”.

Although it’s true that hypersexuality does involve an increased sex drive, it’s much more complex than that. Hypersexuality is much more than an addiction to sex.

For example, if I told you that hypersexuality is a common aftereffect of sexual abuse, would you be surprised?

Hypersexuality has broadly been defined as “‘excesses’ of sexual behaviour”, which can be accompanied by social and personal distress.1 Researchers have acknowledged that the term itself is vague and is often misinterpreted.2

Far too many people are still unaware that hypersexuality can be a response to abuse. Plus, the numerous misconceptions about hypersexuality only worsen how it is seen: you may see us as sex addicts rather than survivors, who are in need of help and healing.

My recklessness towards sex was seen as part of my personality; it was part of who I was

When I was a child, I was sexually abused by our neighbour’s eldest son. There was no violence nor a sense of threat; his approach was one of conditioning. He groomed me into believing that what he was doing was a sign of his affection – I was special, unlike anyone else. No doubt survivors reading this will know that line all too well.

The thing is, once his abuse came to light and my family began to move on with their lives, never once did anyone consider how much it would impact me. I suspect this was due to several factors: chiefly, that it was the 90s and paedophilia wasn’t as widely discussed, and secondly, because everyone assumed that I was too young to remember it. I seemed fine, so I must be have been fine, right?

This isn’t to place blame on my family — abuse of any kind is difficult for families to process. Nevertheless, there was a distinct oversight, especially by medical professionals, of how this experience would shape me. Even when I sought professional help as I got older, not once did anyone suggest that I could have hypersexuality as a response to my trauma. Instead, my recklessness towards sex was seen as part of my personality; it was part of who I was.

I became so convinced of this that my whole personality started to revolve around it. To some extent, it still does. Throughout my school years, all my friends commented on how sex-focused I was, how all my jokes were dirty — I was a “nympho”. Even after leaving school, boys who’d always said they’d never fancy a girl like me then messaged me to say that they always thought I’d be kinky in bed.

My hypersexuality defined my worth while also dissociating me from my identity; I saw myself as an object. I was only good for one thing, which meant that anything beyond that wasn’t meant for me

On the surface, this may seem harmless, and on their part, it may have been intended in this way. However, for me, my hypersexuality defined my worth while also dissociating me from my identity; I saw myself as an object. I was only good for one thing, which meant that anything beyond that wasn’t meant for me. As for who I was and who I liked, I kept forcing myself to accept that I was cisgender and heterosexual because all of my experiences had told me as much — anything else I felt was false, something I needed to ignore and push further down.

I’ve carried that persona with me most of my life. To put that into context, I recently turned 30, and only now am I beginning to separate myself from it. What helped me do this, at least in part, was getting my borderline personality disorder (BPD) diagnosis, which then led me to attend a life skills course. During that course, one of the medical professionals running it finally told me that I was hypersexual; others abused substances like drugs and alcohol, whereas I abused sex.

Since this realisation, I’ve been able to better connect with myself, though it’s still a work in progress. I came out back in 2011, but that still didn’t express the full extent of my identity. It’s only now, this year, that I’ve felt comfortable and accepting enough to recognise that my queerness goes beyond that. Yes, I like women, but I like women as a genderfluid individual and not as a cis woman.

Hypersexuality isn’t a dirty word, nor is it this ‘sex-crazed’ idea that people have formed; it’s a real response to traumatic experiences

I still love inappropriate jokes, and I still talk about sex more than a lot of my friends. However, this isn’t because I feel the need to, it’s because I want to. Of course, there’s the natural oversharing that comes with most BPD cases, but again, I’m now able to recognise it. I’m not relying on sex to describe me as a person because now I know there’s more to me. My body isn’t just there to satisfy others while reinforcing my own disdain for myself — I’m, in fact, worthy of love and respect like anyone else.

Although my reasons for sharing this story now are largely personal, there’s also the need to spread awareness as more sexual abuse cases come to light. Sexual abuse has always been an issue, but this year it’s gotten worse,3 mostly due to a pandemic that’s kept us locked in with our abusers.

Sexual abuse leaves you feeling alone and frightened. I don’t want anyone who responds to their abuse like I did to feel as if they’re lesser for it. Hypersexuality isn’t a dirty word, nor is it this “sex-crazed” idea that people have formed; it’s a real response to traumatic experiences. If you feel like this is you, that what I’ve talked about resonates with you, then please don’t hide.

It’s okay to be hypersexual because of your abuse.

If you think you may be hypersexual, speak to your GP who will be able to advise on a treatment pathway or refer you to therapy or addiction support

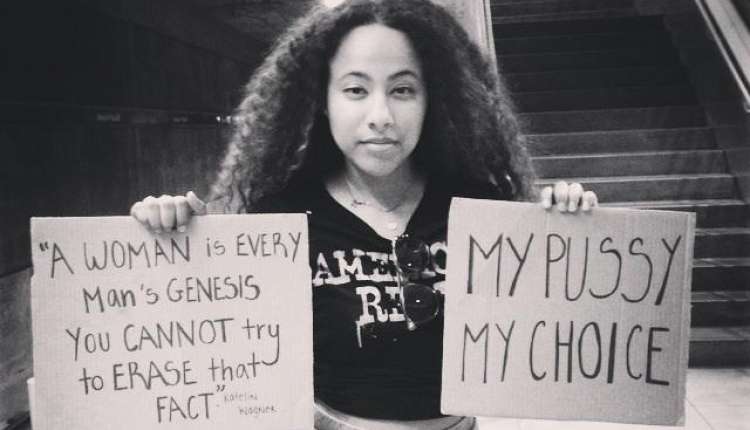

Featured image is an illustration of a white, feminine-presenting person, with long brown hair. They are lying on their bed, curled up on their side, with a slightly pensive look on their face. Behind their back, there are outline illustrations of sexual scenes, which are presented as being the person’s thoughts or daydreams

Page last updated January 2021

Hypersexual disorder is a proposed diagnosis for people who engage in sex or think about sex through fantasies and urges to the point of distress or impairment. These individuals may engage in activities such as porn, masturbation, sex for pay, and multiple partners, among others. They may feel distress in areas of life including work, school, and relationships.

The concept of “sex addiction” is under heated debate. However, in a controversial decision, compulsive sexual behavior disorder was added to the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases. Some researchers see this tendency as a problem of regulating behavior, while other experts wonder whether this behavior derives from a higher sex drive or if it stems from impulse control problems.

Other experts believe that the real causes of the behavior include emotional states, namely anxiety, depression, or relationship conflict. For some individuals, shame and morality may also be involved. Whether the condition exists or not, psychotherapy may be useful for individuals seeking to regulate their emotions and gain insight into their sexuality.

Hypersexuality is not included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. It was previously listed in the DSM-4 as a Sexual Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified with the definition “distress about a pattern of repeated sexual relationships involving a succession of lovers who are experienced by the individual only as things to be used.”

The 2010 proposal for the addition of hypersexual disorder into the DSM-5 included the criteria of uncontrollable sexual behavior. Supporters of the behavior’s inclusion argued that people who engage in this excessiveness suffer from great distress. In the proposed criteria, hypersexual disorder was conceived as a non-paraphilic sexual desire disorder with an impulsivity component.

The proposed diagnosis was not added to the DSM-5. Experts note that there isn’t enough empirical evidence to support the diagnosis. Many do not view it as an addiction and believe it has no similarities to other addictions. Some also fear that the diagnosis would pathologize normal aspects of human sexuality.